Share the page

Controlling Epidemics in the Indian Ocean and Indo-Pacific Regions

Published on

In recent years, the Indian Ocean region has endured epidemics of human and animal diseases, from cholera and the chikungunya virus, to foot-and-mouth disease and rabies. The Sega-One Health network helps to mitigate and control such outbreaks through epidemiological surveillance and alert management. For the next stage in 2024, AFD is providing the Indian Ocean Commission (IOC) with funding to extend health security measures across the Pacific region and Southeast Asia.

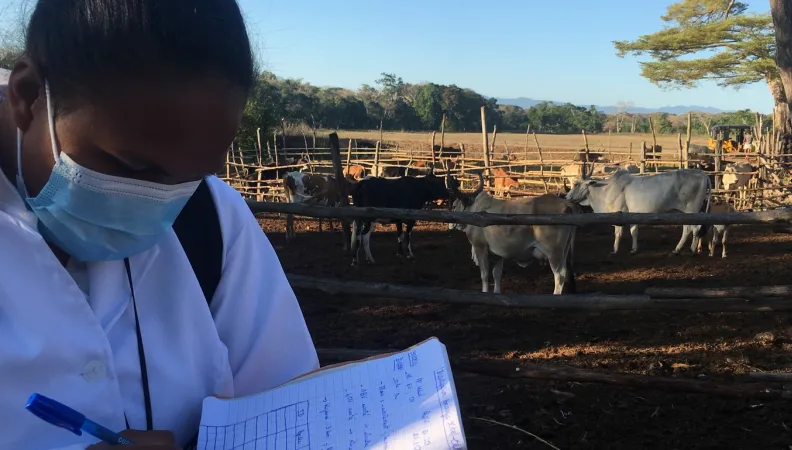

As an epidemiologist and expert for the Health Surveillance Unit (UVS) of the Indian Ocean Commission (IOC), she has been on the front lines in a constant battle against diseases such as pneumonic plague, rabies and Rift Valley Fever. To combat rabies, Nivohanitra Razafindraibe, monitors the treatment of people bitten by infected dogs and leads animal vaccination campaigns.

To prevent pneumonic plague, she has been involved in catching rats that can transmit the disease. As is the case with Rift Valley Fever (RVF), where she treats infected animals and collects samples. Among the key tools are contact tracing, investigation protocols and identifying operational teams.

These field operations are implemented with the support of the national health authorities and 89 health care professionals from the country, who have obtained FETP-Frontline certification, an epidemiological training program delivered by the IOC, together with Madagascar’s National Institute of Public and Community Health, and financed by AFD.

“These professionals have also been required to investigate outbreaks of bovine skin disease, pneumonic plague and glanders,” says Razafindraibe. In the five countries of this region (Union of the Comoros, Réunion, Madagascar, Mauritius and the Seychelles), the IOC has deployed a crack team of 200 trained epidemiologists.

Nivohanitra Razafindraibe is responsible for coordinating and facilitating the operations of this network of epidemiologists and supporting all departments in the country that monitor human and animal diseases, in order to prevent epidemic outbreaks and stop them spreading to other regions.

This is the primary objective of the Sega epidemiological surveillance and alert management network, set up by the IOC and financed by AFD since 2009, three years on from the devastating Chikungunya virus epidemic. Close links between the islands of this region have contributed to the spread of Chikungunya – which translates locally to “walking bent over”. The outbreak also demonstrated that the systems for sharing health information between these countries were insufficient.

Five years later, in 2013, the Sega network expanded its focus to animal diseases and changed its name to Sega-One Health, responding to the need for a global view of these outbreaks, particularly with the resurgence of zoonotic diseases which can be transmitted to humans and account for 75% of emerging diseases in people.https://www.afd.fr/en/actualites/one-health-responding-pandemics-holistic-approach-human-animal-and-environmental-health

In 2018, the network began to look at climate change and border surveillance issues. The Covid-19 pandemic offered a stark reminder, if any were needed, of the speed at which a disease can spread across continents and oceans, evading national health protocols and control measures if such efforts are not coordinated.

Since 2009, AFD, joined by the European Union in 2020, has granted over €30 million in financing to develop this network, which epitomizes the notion of a regional “common good”, says Claire Giron, head of the Projects team for AFD’s Indian Ocean Regional Office.

The latest stage in this vast epidemiological surveillance and response program was launched in February 2024. The IOC and AFD signed a financing agreement in Mauritius to strengthen health security measures in the Indo-Pacific region, amounting to €6.5 million. “This project was designed in view of the lessons learned from Covid-19: it’s imperative that governments and regions of the world collaborate on health security and epidemic prevention,” says Claire Giron.

See also: How do we Measure Adaptation to Climate Change?

With this aim, the Sega-One Health network is joining forces with two other epidemiological surveillance networks, also supported by AFD: the Pacific Community’s Pacific Public Health Surveillance Network (PPHSN) and the Ecomore program run by the Institut Pasteur in Southeast Asia. “This financing will be used to promote the sharing of experience and expertise [to combat] the resurgence of infectious diseases.”

The network promotes the pooling of information and resources. Since 2009, it has produced tangible and concrete results in terms of health surveillance, risk prevention, operational capacity and the technologies deployed.

Mauritius, having struggled with a foot-and-mouth epidemic over the last few years, offers a case in point. As a result of work by the network’s teams, the Mauritius Veterinary Services Division and Madagascan veterinarians, the strain was identified, and 20,000 vaccine and serological testing kits were purchased. According to calculations by the IOC, without the network’s support, the Mauritian economy would have incurred losses of €27 million due to the epidemic, whereas the operation by Sega-One Health only cost €2.5 million.

The regional intervention plan developed in the Comoros amid a cholera epidemic is another prime example. The IOC now has two experts based on the ground, and health supplies have been dispatched, including personal protective equipment and rapid test kits, along with transport and communications equipment. This work has all been achieved in partnership with the Indian Ocean Regional Intervention Platform (PIROI) of the French Red Cross.

This project illustrates the Sega-One Health philosophy to implement coordinated actions between the various players in the region, with the option to mobilize 400 experts in the Comoros, Seychelles, Réunion, Madagascar and Mauritius. According to Rémy Rioux, Chief Executive Officer of AFD, “It's essential to develop multi-disciplinary, cross-regional networks that promote a One Health approach, incorporating human, animal and environmental health for better assessment of health risks.”

The challenge now is to “ensure the long-term sustainability of the network, through financial contributions from IOC member states,” says Claire Giron. In this way, the Sega network can continue its operations beyond those funded by AFD and the EU, at a time when the region’s states and territories are at increasing risk from health threats.